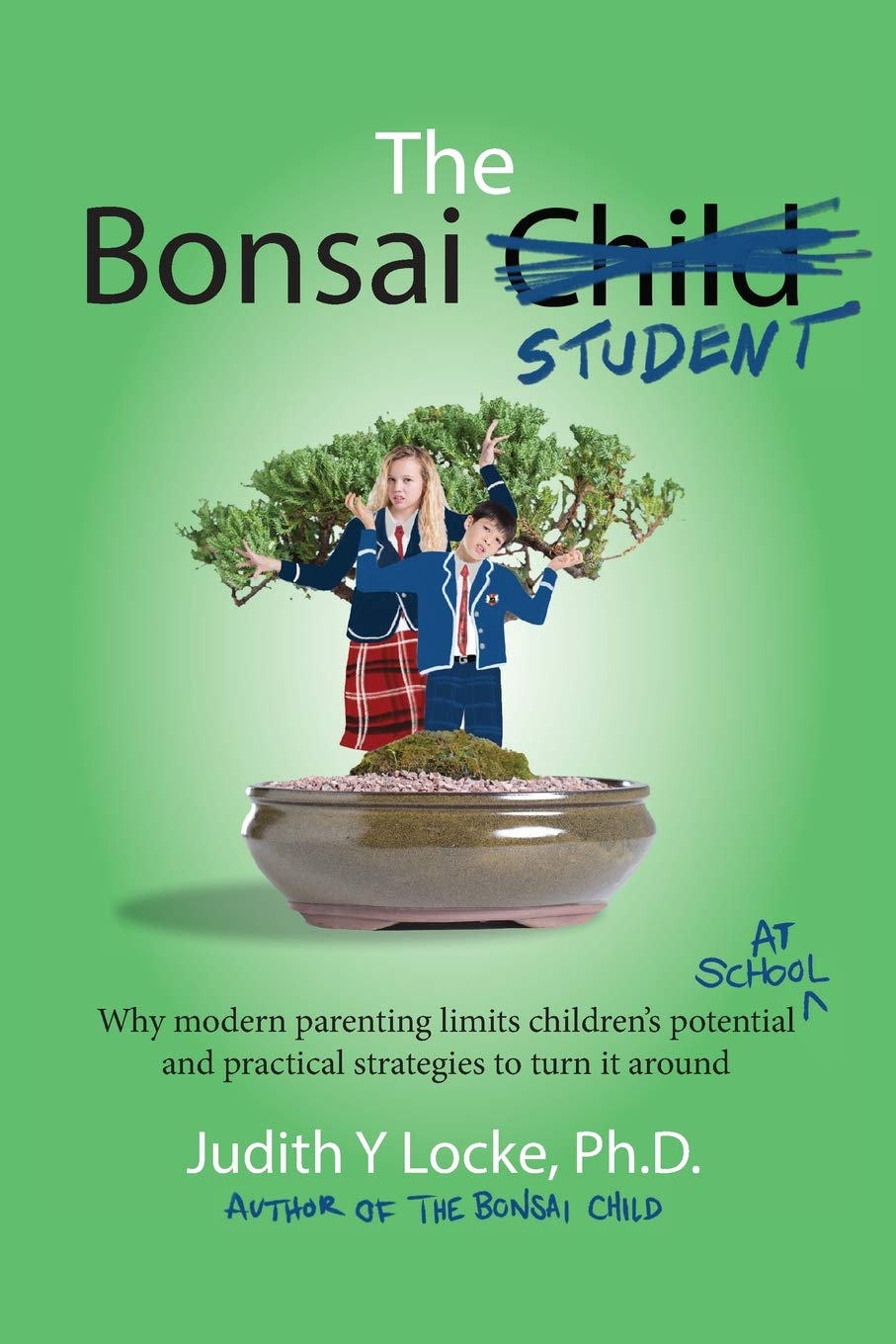

In her latest book The Bonsai Student, Dr Judith Locke offers strategies for over-involved parents to pull back, and encourage responsible, resilient and ready students.

In the best-selling The Bonsai Child, clinical psychologist Judith Locke looked at how over-parenting can stunt a child’s development.

In the sequel The Bonsai Student, she explores what this approach means for a child’s education – and what parents can do.

Dr Locke speaks with Shane Green.

The book is the follow on to the popular The Bonsai Child. It’s a powerful image of what can happen when parents do too much for their child. How common is this approach to parenting?

My research in 2012 showed that approximately 40-60 per cent of the parents at the non-government schools I surveyed, adopted what I would describe as an overparenting approach – which I later dubbed Bonsai Parenting. Bonsai parenting is giving them a perfect childhood via extreme parenting effort. This parental over effort makes a childhood look perfect, but the parenting style inadvertently stunts the child by not allowing them to experience a few ups and downs or learning how to take care of themselves.

But two things are important. First of all, bonsai parenting or overparenting is on a continuum and I wouldn’t say parents are, or are not, bonsai parents. Parents might be overdoing it in one or two areas, such as overhelping with homework, but not in other areas, such as still making their child do a reasonable number of chores. That’s why I wrote both books for parents to assess what they are doing well and what areas might require a bit of fine tuning to ensure they are truly assisting their child develop the essential skills they need for life beyond the home environment.

Secondly, some parents are not bonsai parenting at all but see other bonsai parents and feel guilty for what they aren’t doing for their child. The book will help with this. Indeed, I love it when parents come to me at the end of my sessions for parents and say, ‘Thank goodness! I have been feeling like I am not doing enough for them, but after your session, I realise I am generally getting it right.’

Overparenting – too much of a good thing

It’s interesting you don’t use the terms ‘helicopter parent’ or ‘lawnmower parent’, but rather, ‘overparenting’. Can you explain why the terminology is so important?

Helicopter parenting is a term created in universities to describe young adult students whose parents were still hovering around them. It is a term that has taken off, but it isn’t technically relevant to all parents, because in the child’s younger years you should be hovering a little – such as when you are in a crowded place.

I prefer overparenting because it is simply too much of a good thing – like overeating or over-exercising. It implies that if you pull back a little you will probably get it right, and for most parents who are overparenting, that’s the case.

Terms like Bonsai Parenting can be useful because they are rich in imagery and the image alone might help some parents step back. For example, I created a term recently ‘Sherpa parenting’ – shown when parents carry their child’s school bags into school or taking on their child’s home chores in Year 12. I describe it as potentially allowing children to reach a level of performance that might not reflect their true ability. For example, is a real problem if they receive an ATAR score that is only high because everyone else shouldered some of their burdens – this might result in the child scraping into a course a little above what they are truly capable of doing. University might be trickier for them as they are not used to handling their own responsibilities, so to speak, and the course has them a little out of their depth, making them more at risk of dropping out as soon as the going gets tough. In fact, there’s a whole chapter on getting Year 12 right in The Bonsai Student to truly prepare them for the years beyond school and not just focussing on getting the highest ATAR they can get, which is a danger.

But back to Sherpa parenting – is it a new type of parenting? No, it is still overparenting, but I find that different terms resonate with different parents and I am an ex-drama and English teacher, so I love a good metaphor or analogy!

Well-intentioned over-involvement

The reason for the latest book is that so much of this approach to parenting is played out in connection with education and schooling. You mention that when you worked as a teacher in secondary schools, you’d lament the lack of parental involvement. Not so now, and not always in a good way…

No and this well-intentioned over-involvement in their child’s education is stopping teachers making good professional decisions that are in the best interest of the child. For example, if a child forgets to do their homework, a lunchtime detention is the most effective way to give them a consequence that makes them more likely to do the homework next time. But if a parent interferes by calling the teacher and giving an untruthful excuse why the child didn’t do their homework to save them from the consequence, it’s going to stop the child learning the lesson. It creates a short-term easy life for the child, but at a long-term cost.

Why parents need to know about school

The section of Schooling 101 is incredibly useful. How important is it for parents to understand what actually happens at school, and what is expected of their child?

Incredibly important. Schools are not just about the academic skills of a child, they are there to develop many other aspects such communication and social skills, a love of exercise and being healthy, community mindedness, and a sense of curiosity about the world. You shouldn’t just choose a school for its academic reputation as most schools are about a whole lot more than that.

What 'success' really means

The book explores the idea of what parents think ‘success’ for their child means, and that a sole focus on academic success is very limiting….

Yes. Success is not just about their ability. In fact, the key predictors of a child’s success are much more to do with their internal motivation and the effort they put in as a result of that impetus. Too often, it is the parents’ drive (and nagging) that gets a child to do their work, which mucks up the development of the child’s motivation. There is a point parents have to step back a bit and then there is a point where parents have to accept their child for who they are, even if they are not very academic. That skill or interest might come later, and it is important for parents to remember that life is not a straight line and many parents themselves, were pretty slack at school and went on to be successful. It is usually the essential skills such as resilience and self-regulation that make people successful beyond school and not necessarily only ‘good school results’.

The essential skills

Yes, in fact you name five essential skills your child needs at school and beyond…

It’s one of the most important chapters in The Bonsai Student. I explain what they are – resilience, self-regulation, resourcefulness, respect and responsibility – and how bonsai parenting might muck up a child developing these skills. I also give parents some key areas to look for in a child to check if they are developing each skill and what to do to help them develop each one.

Don't despair

Many parents will recognise some of the parenting traits you identify as contributing to a bonsai child and student. What feedback do you have for parents who have that ‘oh no, this is me!’ moment? Is it ever too late to change?

It’s never too late but it does get harder the older your child is, so I would strongly recommend reading both of my books earlier rather than later. But don’t despair at whatever their age. As in The Bonsai Child, I detail really practical ways of developing children’s skills and making the family home more harmonious in The Bonsai Student – such as better ways of managing that mad morning rush before school or the whole homework situation. Change won’t happen overnight necessarily, but it will happen if you put your mind to it.

About Judith Locke

Dr Judith Locke is a registered clinical psychologist, former teacher, school counsellor and workplace trainer. She is the director of Confident and Capable®, a company specialising in psychological training solutions for parents, children, teachers, and others in schools, childcare centres, government and community organisations, and private companies.