How do kids think about kindness? Summer Braun, Michael Warren and Kimberly Schonert-Reichl asked fourth and fifth graders — and the results showed they were particularly attuned to compassion and inclusion.

Kindness is sometimes dismissed as a simplistic virtue comprised of ‘being nice’. But how do kids think about kindness — and could understanding kindness help us to teach and promote kindness more effectively?

In a study recently published in the Journal of Positive Psychology, we found that children’s thinking about kindness encompasses a rich set of selfless, altruistic orientations that can benefit others, schools, and societies.

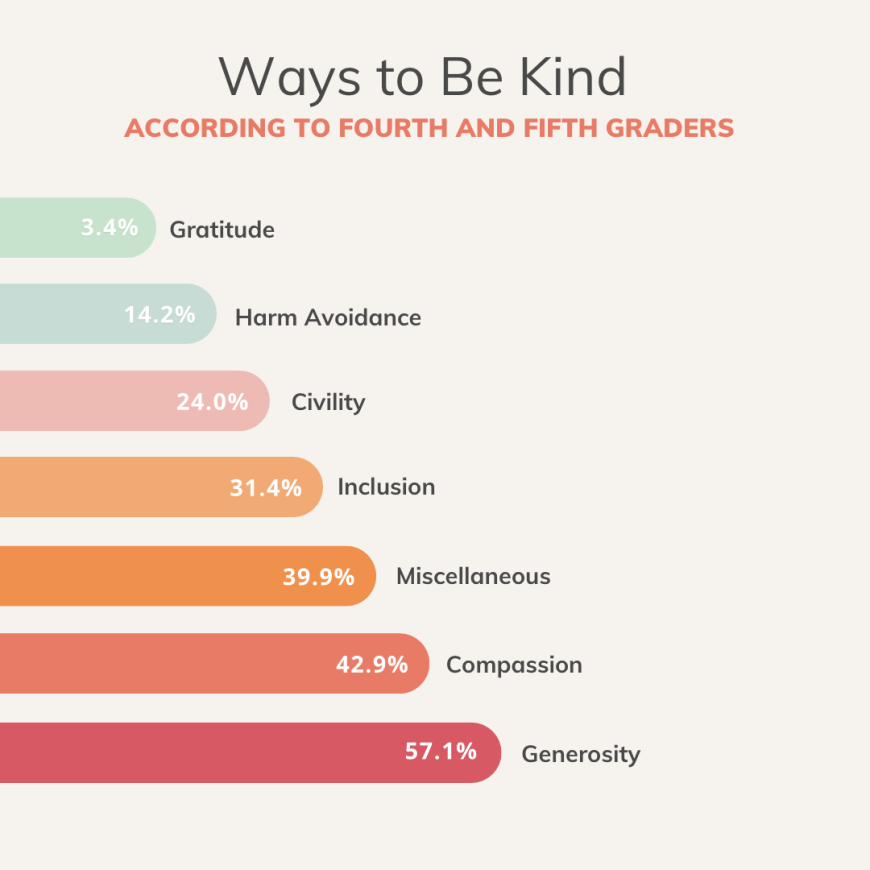

We explored the spectrum of children’s understandings of kindness by asking 320 fourth- and fifth-grade students from two school districts in British Colombia, Canada, to list the ways that they can show kindness to others. Our findings showed that many children described kindness in terms of generous (57 per cent of children) and compassionate (43 per cent) behaviours. For example:

- ‘Share food’ (generosity)

- ‘Congratulate people’ (generosity)

- ‘Listen when a friend is sad’ (compassion)

- ‘Help them with a question they’re stuck on’ (compassion)

Children’s thinking about kindness also expanded to virtues of inclusion (31 per cent), civility (24 per cent), and harm avoidance (14 per cent). For example:

- ‘Eat lunch with them’ (inclusion)

- ‘Respect others’ feelings’ (civility)

- ‘Don’t be selfish’ (harm avoidance)

- ‘Don’t bully’ (harm avoidance)

We also examined classmates’ and teachers’ perceptions of each child. Interestingly, children whose kindness responses attended to others’ vulnerability (in other words, they mentioned compassion and inclusion as ways to be kind) were identified as particularly kind by their classmates, whereas children’s kindness responses were unrelated to teachers’ ratings of kind behaviour.

These results suggest that classmates, more so than teachers, notice and appreciate others who think about, and therefore enact, kindness in ways that are compassionate and inclusive. Perhaps this is because classmates are more likely to be the beneficiaries of children’s compassion and inclusion than teachers. Compassion and inclusion are responses to suffering and isolation, respectively, that would not likely go unnoticed by the recipients of such kindness.

What implications does this research have for promoting kindness in the classroom?

The way children describe kindness aligns with themes covered in social and emotional learning programs that focus on cultivating children’s kindness. The most common kindness responses identified in this study (generosity, compassion, inclusion) may be solid entry points for education about kindness, as fourth and fifth-graders identified them as particularly relatable and widely agreed-upon expressions of kindness.

In contrast, the least common kindness responses (harm avoidance, gratitude, and perhaps forgiveness) may reflect areas of growth that could require additional scaffolding and support to expand children’s notions of kindness into these areas.

Our findings also imply that efforts to expand children’s thinking about kindness to incorporate compassionate and inclusive actions may be most impactful and appreciated by their classmates. Indeed, existing research has already demonstrated that there are social benefits for those who are viewed as kind, such as greater acceptance by their peers.

When asked about kindness, children listed an average of roughly three ways to be kind to others, which means that they think about kindness as much more than simply ‘being nice’ — and also suggests that educational efforts could go a long way toward further expanding their conceptualizations of kindness. Understanding how children naturally think about kindness is important foundational knowledge for teachers and parents to work from in their efforts to build kind, happy classrooms.

About the authors

Summer S. Braun, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology and affiliated with the Center for Youth Development and Intervention at the University of Alabama.

Michael T. Warren, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology and affiliated with the Center for Cross-Cultural Research at Western Washington University.

Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, Ph.D., is the NoVo Foundation Endowed Chair in Social and Emotional Learning and professor in the community and applied developmental psychology (CADP) program in the Department of Psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

This article originally appeared on Greater Good, the online magazine of The Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley.

Like this post? Please share using the buttons on this page.

Stay up to date with our newsletter here