Procrastination looks different for everyone, writes Dr Deborah Trengove. She shares her top procrastination-beating tips.

Does your teenager have trouble finishing assignments, run out of time to prepare for tests or repeatedly leave things to the last minute? If so, they may need help to tackle a procrastination habit.

Procrastination is common: most of us procrastinate about something, doing the housework, making an awkward phone call or perhaps going to the gym. For many school and university students, it is a frequent occurrence, with around 50 per cent procrastinating sometimes, but with no great harm done. However, for 25 per cent of young people, procrastination is a chronic habit and causes significant issues. As not all procrastination stems from the same source, it is important to dig a little deeper into the different causes of procrastination to get on top of it.

Procrastination can be defined as ‘voluntarily delaying an intended course of action, despite expecting to be worse off for the delay‘ (Steel, 2007). For students, the consequences are wide-ranging. Many teenagers have shared with me the emotional costs of the stress, guilt, disappointment and anxiety they experience. Academic costs come in the form of missed deadlines, rushed and poor-quality work, underachievement and compromised goals. Furthermore, relationships with teachers and families suffer as promises and expectations go unfulfilled.

It is easy for parents to focus on the method of procrastination as the source of the problem: the hours spent on social media, streaming shows or gaming. There are also other forms of avoidance which are more deceptive: these include organising books, chatting to families or even sleeping, to delay study. These give us the how of avoidance but not the why. In order to break out of the procrastination trap, we need to first identify the underlying cause, which is not the same for everyone.

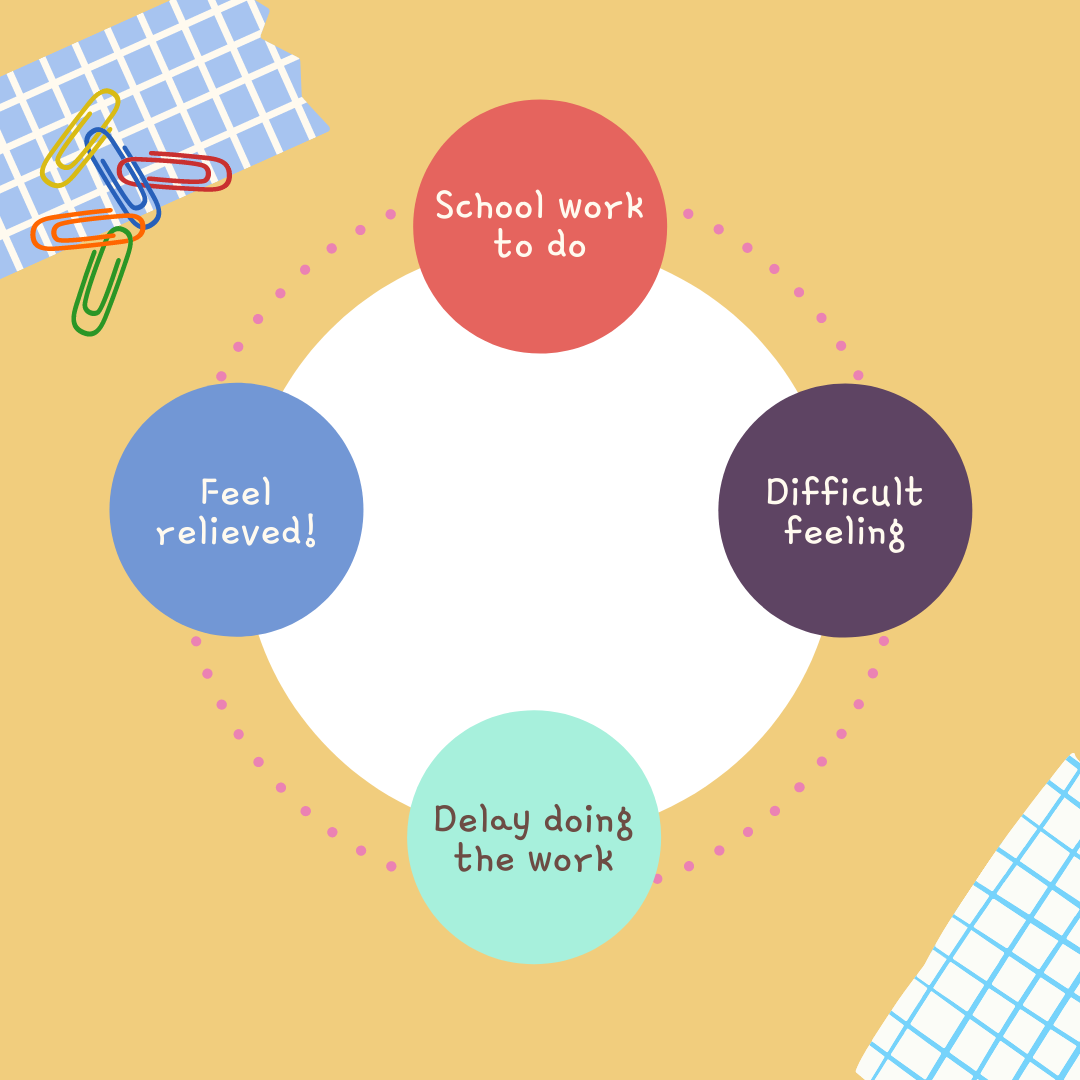

The diagram below sets out the cycle of procrastination – note that avoidance follows the experience of a difficult feeling that is associated with study tasks. The immediate reward of the act of procrastination comes in the form of relief from these difficult feelings when study is delayed – despite knowing the situation will be worse as a result.

What are these difficult feelings? They are a number that have been identified by various researchers such as Sapadin (2012) and Bernard (1992). They include avoidance of potential failure, disapproval, rejection, feelings of inferiority, difficulty or boredom. In my experience, the three most common types of procrastinators are:

The worrier: who feels stressed by so much to do and lacks confidence in their own ability. The challenge is to take risks and focus on the process of learning.

The dreamer: has lots of good intentions but frequently feels annoyed by boring or difficult tasks. The challenge is to tolerate feelings of discomfort and stop making excuses.

The perfectionist: often feels overwhelmed by unachievable goals, believing everything has to be perfect. The challenge is to find a middle ground and aim for excellence, not perfection.

Each of these types of procrastinators can benefit from different strategies. The perfectionist can use time limits for specific tasks and consciously practice learning to accept mistakes. The worrier can reward themselves for taking a small risk and focusing on their personal growth. The dreamer can learn the difference between feeling good (comfortable) and feeling good about themselves and changing their self-talk from ‘I’ll try’ to ‘I will!’

Raising this topic with teenagers can be difficult, as adolescents can easily become defensive. However, the academic costs and emotional stress are very real, so it is important to address habitual procrastination. Try to help your young person articulate the underlying cause of their avoidance in a non-judgemental way or consider having a shared conversation with a trusted teacher at school. A few sessions with the school psychologist may also help to work out underlying causes and develop new routines.

Encourage your teenager to identify 4-5 practical changes they are willing to implement, balancing accountability with encouragement.

Here are my top 10 procrastination-beating strategies:

- Breaking big tasks down into small ones

- Using favourite distractions as rewards

- Using rewards along the way, not just at the end of the week or term, often too far away

- Worst-first: starting with the tasks always left to last

- 10-minute technique: beginning with a 10-minute activity to get going

- Changing the study environment – at school, in a library, a different room – to limit distractions and set new routines

- Implementing 30-minute study blocks with specific activities for each burst

- Setting a specific and regular time to start schoolwork, the earlier the better

- Adopting active study methods – they are more engaging

- Making two lists: a daily list and a weekly list, which are connected and specific.

Procrastination can be a tough habit to beat, so be prepared for your teenager to relapse, but don’t get discouraged. Procrastination can worsen over time if not addressed, so it is vital to help young people lay the foundation for achieving their potential, reducing stress and building confidence for study now and into the future.

About the author

Dr Deborah Trengove is a former school psychologist and school wellbeing leader.

Deborah’s previous articles for The Parents Website include How parents can help kids make good friends and Lessons from lockdown: The good things we’ve discovered.

References:

- Bernard, M (1992) Procrastinate Later! How to Motivate Yourself to Do it Now. Schwartz and Wilkinson

- Sapadin, L (2012) How to Beat Procrastination in the Digital Age. Psych Wisdom.

- Steel, P. (2007). The Nature of Procrastination: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory Failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 65-94.