Finland will only teach handwriting in the first year of school. What should happen here? Shane Green reports.

Children often learn to swipe a touch screen before they learn to hold a pencil. Does this mean the end of handwriting?

Academic Noella Mackenzie believes that the answer is a resounding ‘no’.

The digital revolution has swept through our classrooms, turning upside down the way students learn and communicate. Digital natives, they operate in a multi-screen, multi-device world, where the keyboard is seemingly king.

Dr Mackenzie, a Charles Sturt University academic, has seen the transformation close up: first as a primary school teacher, then as an early years literacy specialist and now as a senior teacher educator and researcher in literacy.

She argues that not only does handwriting have a future, it is also an essential part of literacy, providing a foundation to learn in other disciplines.

‘What I’m arguing is that it shouldn’t be either/or,’ she says, ‘it should be both. We should be instructing our children in efficient ways of handwriting and efficient ways of using a keyboard or tablet.’

Working in early literacy, Dr Mackenzie developed a fascination with the role of writing. She saw that when a teacher taught writing well, a child’s literacy was strong.

But if there was just a focus on reading, you would get a good reader, but not necessarily strong literacy.

Invariably, when she spoke to educators, she would be asked: what about handwriting?

Beyond referring to other people’s publications, she felt she needed to draw on her own research, and the stars aligned with news that from this year, Finland would only teach handwriting in the first year of school.

As she notes, Australia is quick to embrace what’s happening in Finland. But there are big differences. Children in Finland start school aged seven, after two years of five-days-a-week preschool that is government funded.

A colleague in Lapland told her that by the time Finnish children start school, many can read and write. Contrast that to Australia, where Dr Mackenzie says some children can’t write their own name when they enter a classroom for the first time.

Dr Mackenzie will travel to Finland in August to further investigate the change in the curriculum.

Survey of Teachers and Parents

Conscious that her research on what was happening in Australia needed more than anecdotal evidence, she set up an online survey for teachers, retired teachers and parents. (The survey closes on Thursday 30 June 2016).

So far, close to 1000 people have responded, across all school types.

What she has found is confusion. The message from teachers is that they don’t know what to do.

‘We don’t know whether we should be teaching handwriting, or because of keyboards, we should be just teaching keyboarding,’ teachers in the survey have told her.

‘What some teachers are telling me is that they are doing neither,’ says Dr Mackenzie.

And parents are concerned. They want their children to be able to write efficiently, but don’t know how to help them.

Dr Mackenzie says the media would like us to believe that with so much technology in schools, children aren’t handwriting.

But the reality is the opposite, even in schools that provide the best technology with the best support.

The research suggests that children from the age of eight spend at least 50 per cent of their school day writing.

‘The reality is that in all subject areas, there is writing involved,’ says Dr Mackenzie. ‘And in most cases that’s being done by pen and paper intermittently juxtaposed with keyboards and tablets.’

The Benefits of the Written Word

Beyond that practical consideration, children also learn more through handwriting. When children learn letters, they learn the name of the letter, the sound it makes and its shape.

Contrast that with using a keyboard: the feedback you get from your finger is the same.

There is also evidence that things written by hand are better remembered, says Dr Mackenzie. Consider the shopping list left at home. ‘We can remember what was on it because we wrote it,’ she says.

The aim is for a child to get an efficient handwriting system, creating letters and words easily and fluently, that someone else can read.

That in turn allows them to concentrate on creating meaning. Otherwise, their working memory is used on how they should write a word, what comes next.

‘Those kids who are struggling with getting their words on paper are struggling with the science, they’re struggling with the social science, they are struggling with the content,’ says Dr Mackenzie.

Her message is the importance of handwriting in overall literacy, and the balance between communication modes. ‘I don’t know about you,’ she says, ‘but I’m sitting in front of two keyboards, I’ve got a tablet, I’ve got a smartphone, I’ve got a notepad and I’ve got a pen.’

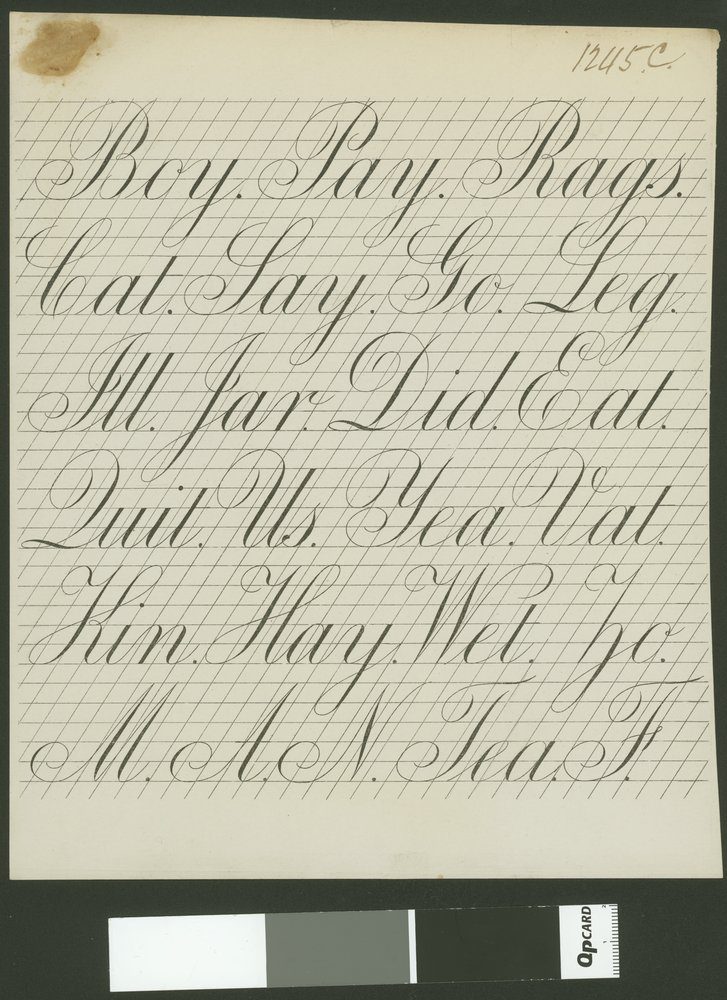

Main image: 1878 lithograph of examples for practice in cursive handwriting, Robert Jones. Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria slv.vic.gov.au