Here, Maggie Dent one of Australia's leading parenting educators, explores the modern tendency of overprotecting children, which can hinder their development and resilience

Let’s begin with an honest truth – every parent is biologically wired to want to keep their children safe in the world. I was a child of the 1950s, and while this was still a reality for parents then, the expectations of how to protect our kids were very different.

If you do get a chance, I encourage you to read Jonathan Haidt’s book, The Anxious Generation. I have followed his work for many years and have written about the concerns that he has had about how we are raising our children. He has gathered an incredible amount of data and research to show that today’s kids are struggling to grow up to be healthy adults. The statistics that he shares in his book are pretty disturbing. Given that I’ve just done the research about how our teens are travelling globally for my new book Help Me Help My Teen, a part of me was not surprised.

The arrival of the digital world, especially into childhood, has been the largest social experiment ever conducted on us as humans. While Dr Haidt blames the arrival of smartphones for the massive decrease in the mental wellbeing of our teens, especially our girls, he has another deeper message. We are messing up childhood.

Understanding child development

Thankfully, we have shifted paradigms from the ‘focus of behaviourism’ in childhood, which assumes that the only way to raise healthy children is to punish their bad or difficult behaviour and to reward their good behaviour. Given that we are not rats, which is what that theory of learning was based on, it has created many problems in the long-term social and emotional development of children. The main focus of this approach was forced compliance, usually through the use of fear or punishment that children should just do as they were told. No human in the history of humankind responds well to being told what to do.

Cooperation is much more likely to happen when an individual is treated with respect and requested rather than commanded; guided and mentored rather than forced.

This has a much better chance of occurring when there is relational safety – which means the directive comes from a safe human.

The science of child development now shows very clearly that healthy attachment is far more important in the healthy raising of children who are not emotionally scarred in childhood. The world is much better informed about the impact of trauma and adverse childhood experiences on the healthy development of our kids. Unfortunately, there is a flipside to this in the parenting landscape around the concept of healthy attachment that has confused so many parents. Many believe that being tender and loving means that you need to make sure your kids are happy all the time. This priority means that many parents, whether consciously or unconsciously, are striving to create perfect, trauma-free childhoods where kids do get the biscuit before dinner or we cave in and give them whatever it is they are screaming about in order to restore their happiness.

No adult human is happy all the time. Our children are not meant to be happy all the time.

When our kids struggle with big feelings after a parent has put a boundary in place, and they scream and possibly throw a tantrum, rather than see this as a failure as a parent, we need to see this as a sign of a parent doing their job. Many of today’s teens are struggling with frustration intolerance. This means that when as children, they struggled with big feelings based on frustration (especially around not getting their own way, not getting what they want or coming up against a boundary like bedtime, or time on screens), many parents have found it just too hard to hold that boundary, and they have given them what they want. So, in adolescence, they have a very low tolerance for feeling frustrated. We only get better at managing frustration in our lives by experiencing it – especially right through childhood.

The pressure of the perfect parent perception has a lot to answer for. The child struggling with a tantrum in the shopping centre is not a bad child who needs a smack, they are a child struggling to regulate themselves. It is developmentally normal for children to struggle to regulate themselves because they have an underdeveloped cognitive capacity. So, this shopping centre tantrum needs to be seen as something normal, not something abnormal that needs to be stopped immediately. So, when not only parents but other grown-ups can reframe that perception that a child is being naughty into ‘that is a child not coping with their world right now’, we can have more compassion for both the child and the parent.

Problematic ‘safetyism’

Safetyism is a term that was first used by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff in their book, The Coddling of the American Mind: ‘Safetyism refers to a culture or belief system in which safety has become a sacred value, which means that people are unwilling to make trade-offs demanded by other practical and moral concerns’. Dr Haidt writes in The Anxious Generation that a key way of raising healthier, happier and more capable teens is to rewire childhood back to days gone by.

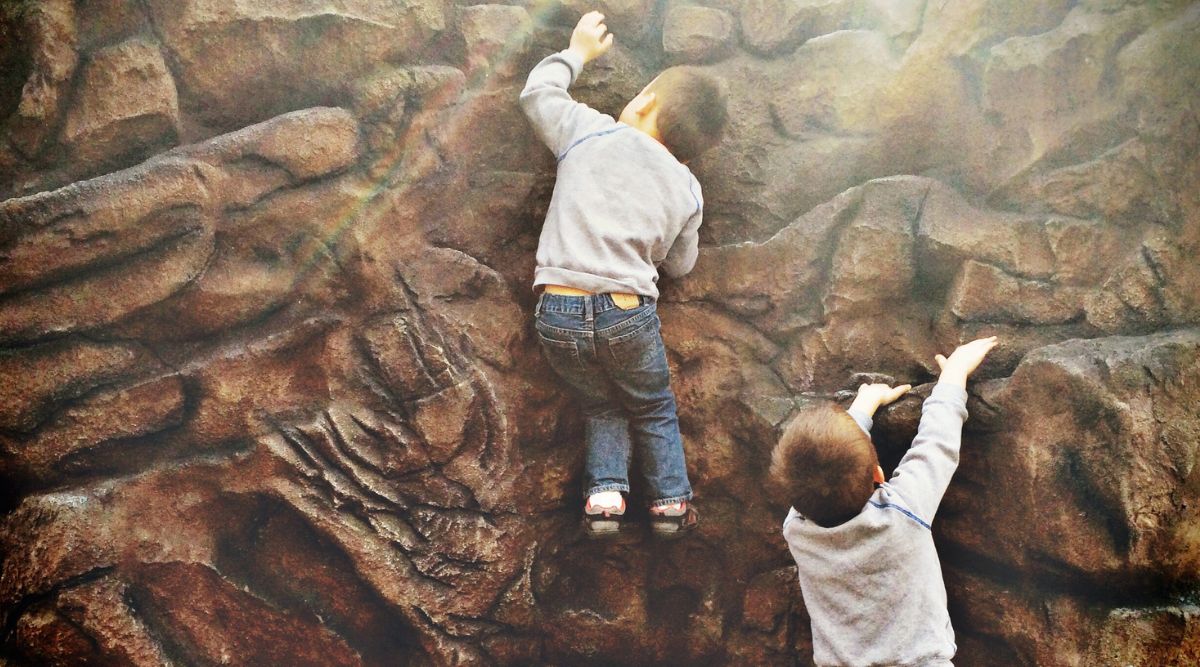

One of the biggest shifts that occurred in childhood happened when some figure of authority created an urban myth that children needed to be more protected in the playgrounds in their schools, their neighbourhoods and their communities. I have been writing about why this was a disastrous decision for children for over 20 years. Children are biologically wired to take themselves to the edge of their own fear in nature and on playgrounds. When we removed the long monkey bars, the wooden seesaws, the big metal slides and many of the things that allowed kids to spin vigorously, we created a fear for parents and kids. Modern trampolines all have sides, and interestingly enough, the injuries that occur are more regular than they were before they had sides. Why? Kids think the sides will keep them safe all the time! Kids need to learn to navigate risks with some guidance and some autonomy. Nothing is ever totally safe.

The occasional natural consequence with ouchies, grazed knees and bumps and bruises were not a sign of poor parenting. They were a sign that a child was learning to navigate the world with their body, and learning to make better choices after each moment of discomfort.

Of course, it’s scary when your child wants to climb higher than you feel comfortable with, and yet if we trust our kids, they will mostly take themselves to where they feel safe because they have an inner warning system that is unique to every child. Yes, the rooster kids who are fiercely brave and confident will scare the heck out of you and may occasionally break a limb. Yes, those gentle, sensitive lambs will take longer to develop their bravery; however, in their own time, in their own way, they will grow.

The best opportunity to grow healthy, capable and resilient kids is to create as many play opportunities as possible in the outside world with some degree of risk, with multi-age children of all genders, with as little adult supervision as possible! No, really, it is. Research shows that older children are biologically wired to become the carers of younger children when there is no adult present. Younger children are wired to learn from the behaviour of older children not only in how to navigate the world physically, but also how to communicate with others, how to navigate conflict and how to sustain play. In these environments they all have opportunities to lose, to win, to laugh, to cry and to ultimately grow in so many ways.

The best way to overcome safetyism is to set your kids free to allow them to stretch and grow. Frequent, small steps of bravery can soon become a giant leap of courage.

Time to play

One of the most significant shifts in childhood since I was raising my lads in the 80s and 90s is the pressure to be a part of organised activities. Of course, there was always sport, music, dance and organised groups like Brownies, Cubs, Girl Guides and Scouts.

Extracurricular activities have now been super-sized and the expectations of the age to start our kids in these activities have moved downwards.

If you have a high-energy child, they are properly able to cope with some organised activities when they are 3 to 4, but most kids will have difficulty concentrating at the end of a day of childcare or school, under the age of six or seven. Not only are they starting earlier, but many kids also do several extracurricular activities. I’ve spoken to a number of parents who have realised that, much like the push-down of formalised learning, too much too soon is not good for our kids.

Allowing kids time to play without adult supervision in the outside world can be a deceptively brilliant way to help kids regulate themselves after school, to experience moments of fun and joy, to nurture and develop friendships and to spend time in fresh air. I celebrate the primary schools that have some afternoons where the kids are able to play on the school playground for an extra half an hour and I absolutely celebrate the ones, who organise a coffee van to be present as well for parents.

When we hurry our kids up to be a part of organised activities, we are stealing precious time for them to be fully present in their own world. Another key aspect of having time to play is giving children the autonomy to choose what they want to do. I have spoken to paediatricians and allied health professionals who have found a link to some significant mental health challenges later in life, because they never had a voice or a choice. Too much organisation, too much scheduled time can cause more stress for kids and their parents. I am aware that the pressures of the modern world need more parents working, so creating opportunities for extended play can be difficult. I do celebrate all the wonderful grandparents caring for kids after school and also those wonderful humans who do out-of-school hours care for families because they seriously know about the power of play and the importance of connection, autonomy and freedom.

Where can you create more time for your kids to play in your busy week?

Just a small step and the magic of ‘…yet’

One of the toughest parts of parenting is watching our kids struggle and fail. Even though we know that they are learning to navigate these difficult moments, it can still be really hard. Every part of our being wants to rush in and fix the problem, cheer them up or minimise their struggle.

In my Exploring Children’s Anxiety seminar, I share the danger of avoidance when our kids meet a challenge no matter how logical it may sound. When your child is struggling to go on the soccer field, or into the dance studio or birthday party they were really excited about, often we can think they are not ready for that and it is just simply too hard. This is especially true when we are offering wonderful encouragement, but they are still reluctant. Rather than avoidance of the activity though, we can validate that they are finding it hard, and then we suggest they do just one step towards braveness. ‘I am here and I want you to just run out on the field (or dance studio or birthday party) for two minutes! If you are still feeling uncomfortable, you can come back to me, and we will leave.’

When a child says, 'I can’t do it' or 'it’s too hard', remember the magic of the word ‘yet.’

‘I know you are finding this hard, and yes, it’s frustrating when we can’t do something we want to do, but I want you to remember the word “yet”. No one can do anything complicated the first time. No one can cross the long monkey bars the first time. No one can ride a bike without training wheels the first time. However, with practice, they gradually get better. So, it’s not that you won’t ever be able to do it – it’s that right at this moment – you are finding it hard and you can’t do it YET.’

The very best way that we can help our children stretch and grow is through safe, meaningful relationships. The safer they feel, the more likely they will respond to us and the more energy they will have in their nervous system, to stretch and be brave. One of the best ways of doing this in the busyness of life, especially for working families, is to create pockets of joy when you can.

Children are way more capable than the modern world gives them credit for and by giving them life skills and competence (especially in how they move their body or how they sing or dance), we can build an inner sense of self that then creates confidence and genuine self-worth. So, mums and dads, take more deep breaths and encourage those tiny steps of bravery so that one day, they will be brave enough to leave home and live their own lives.

About Maggie Dent

Maggie is one of Australia’s favourite parenting authors and educators, with a particular interest in the early years, adolescence and resilience, and is known as the ‘queen of common sense’.

This article was reproduced with permission and originally appeared at maggiedent.com.

Like this post? Please share using the buttons on this page

Stay up to date with our newsletter here