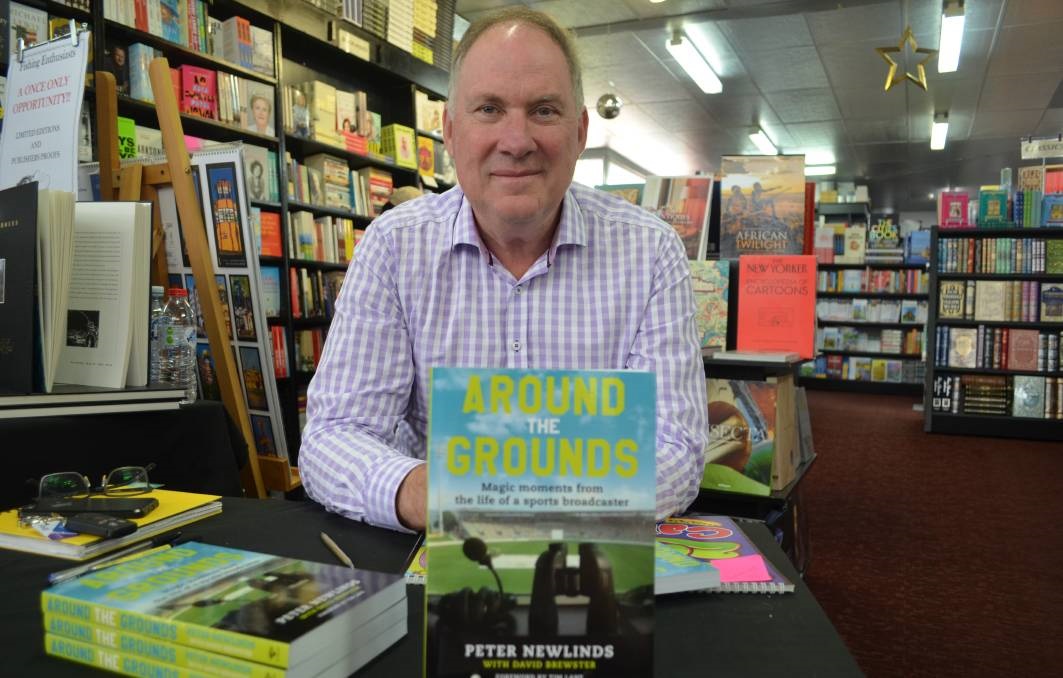

We’re publishing book extracts to give you a break in these trying times. Peter Newlinds is one of Australia’s best known sports broadcaster. In this extract from his book Around the Grounds, published by Bad Apple Press, Peter remembers a school holiday job made for a sports-mad teenager – part of the ground staff at cricket Test matches.

Life inside the scoreboard

By the end of my three weeks of work experience all I wanted was for this combination of grown-up freedom and adolescent dream-world to continue. There was more good news afoot. Having proven myself as a good, reliable worker, I was offered some ongoing part-time work with the ground staff.

The highlight of that Elysian summer was working during the first test between Australia and India in early January 1981. For this game I was on regular ground-staff duties, among other things standing by ready for action in case it rained and the covers had to go down. Greg Chappell made a typically majestic double century, while for one last time (though they didn’t know it) the SCG faithful had a chance to appreciate and applaud Doug Walters as he put together a score of 67. It was a fitting farewell innings on the ground that was his as much as anyone’s. Kapil Dev, like Imran Khan and Botham, another of the great all-rounders of his time, took five wickets for the visitors but it wasn’t enough. Australia won the game by over an innings inside three days.

Before play on the first day I went out to the middle with my workmates. It was enough just to stand out there in front of the early crowd of 15,000 or so, but when a stray practice ball happened to roll my way and I was able to underarm it back to the nearest player – to a cheer from the crowd – I felt that I was pretty much an integral part of the action. Later, during the lunch break, I was asked to repaint the crease lines onto the pitch so I headed out to the middle with a wide paintbrush and bucket of chalky white paint. This job isn’t as easy as you’d think. By now the crease area, pummelled by the fast bowlers’ front feet, incorporated a crater about half an inch deep and with no solid bottom. The more rubble I swept away, the more there was. In the end I just painted as best I could across this ditch, but the line didn’t look very straight. One of the umpires appeared beside me in his black trousers, white shirt and big white hat. He looked down at me, smiled and asked how I was going. I said I wasn’t sure if what I’d done was good enough but, in this pre-DRS world, he seemed satisfied.

There was an incident on that first day that still stops me in my tracks when I think of it. Indian batsman Sandeep Patel was 65 not out and facing Len Pascoe bowling at great pace from the Paddington end. Pascoe bowled a short ball that Patel tried to hook. However, he misjudged his shot and was hit on the lower side of his unprotected head, falling straight to the ground. After receiving urgent medical attention he was able to walk off for further treatment, unsteadily holding a towel to his head. He recovered well, going on to make 174 in the Adelaide test later in the month. Before the advent of helmets, incidents such as this were all too common and always unpleasant, however this one has an eerie symmetry (similar score, same ground, same end) to the shocking death of Phillip Hughes thirty-three years later. There’s the finest of lines between drama and real tragedy.

Before play on the third day of the game I was out in the middle again when Greg Chappell came out, followed by Allan Border wearing shorts and thongs. I have no memory of what they were discussing, but what I do remember is that I’d never heard language quite like it. I had become used to swearing amongst the ground staff but these two raised the stakes a couple of levels. They were friendly, though, Chappell turning to me at one point and asking how I was going. I was too starstruck to answer properly.

The old SCG scoreboard was one of those grand structures unique to the game of cricket. For most people it was the first thing they looked at when they walked into the ground. It was a storyteller, its imposing presence at the Randwick end of the ground keeping spectators and players up to date with the state of play for close to sixty years, until it was replaced by an electronic board in 1983. Any photo that you see of it now is perfectly stamped with those clear white name boards spelling out the essential story of a game at a moment in time. Manual scoreboards still operate at major grounds around the country, and they are quaint and really nice to look at, but for me they don’t evoke the purpose and clarity of this beautiful building on top of the Hill.

It hadn’t taken long into my time with the ground staff for everyone to work out that I was a pretty keen follower of cricket. More than that: I was all over it. In the way of the keen teenager, I had an encyclopaedic knowledge of the game, its history and the players. Sometime during that 1980–81 season someone suggested that this passion for cricket, combined with my youth and agility, made me a good option to join the scoreboard crew. I wasn’t going to say no to a job that would basically allow me to watch days and days of cricket from one of the best seats in the SCG.

The scoreboard was essentially a two-storey concrete building accessed by a long staircase at its rear with a door firmly locked shut at the bottom. Inside it felt like the size of a substantial house, though I always felt it was more like a castle. The scoreboard foreman was Jack Bryson, an old-school operator who was strict but not unkind. The scoreboard was certainly his castle, and in regent style he was always stringent about who was allowed to breach its walls. Sometimes friends of mine would ask if they could visit but Jack was never keen on the idea, while on one occasion two police officers basically invited themselves in. Undaunted by the uniforms, Jack told them in no uncertain terms to turn around and get out.

The board was managed from two levels connected by a steep, narrow staircase, with most of the action taking place on the lower level. Its operation on match days was the responsibility of a team of about six ground staff, led by Jack. This group’s job included everything needed to maintain the board during play, including setting up and installing the players’ nameplates, updating the batsmen’s scores and the bowlers’ figures and, of course, keeping the current score up to date. It was a quiet, focused and industrious workplace, though there was plenty of ongoing cricket chat. The only time the pace really picked up was at a change of innings, when we had only ten minutes to move the long, narrow – and heavy – boards, each featuring a player’s name, from the bowling side of the scoreboard to the batting side and vice versa.

The top job in the scoreboard involved identifying the fielders. Each player had a light beside his name and when the ball was fielded, an operator would push a button to activate the relevant light. That, of course, required that the operator was able to identify each player, which is not always easy when everyone is wearing cricket whites. During my time this job was the domain of Peter Devlin (PD), who I had got to know through lunchtime net sessions during work experience. Peter was a very good first-grade cricketer for Randwick, and later went on to be the head curator at North Sydney Oval. He was the only operator allowed to do the job because of his accuracy and his focus; Peter didn’t talk much. My usual role was to maintain the current batsmen’s scores and total score. I also had to operate the lights indicating which batsman was on strike. This was a task that also required good concentration, if not at the same level as PD’s. You had to learn pretty quickly how to pick one batsman from the other for each partnership: a particular bat brand, subtle differences in mannerism or a certain gait were all useful cues. Other operators looked after the bowling figures, dismissed batsmen, overs bowled and so on. I would work for two sessions of a day’s play and have one session off. My downtime was spent on a long, elevated sofa directly beside the sundries total, which I kept updated during that time. The view was not only private but panoramic, straight across the ground to the handsome green-roofed pavilions of the members area and beyond to the evolving skyline of the city.

There was a telephone on the wall next to where I sat that connected the scoreboard to the outside world. One job I relished was to ring the dressing rooms before the start of a match and have the 12th man from each team give me the batting order. We also used the phone to check in with the official scorers to make sure all our numbers were in sync with theirs. (ABC Radio were always very willing to point out if a number on the board was incorrect.) Occasionally, in those days long before the internet, we’d receive a call from a media outlet wanting a score update. I remember a BBC producer ringing a few times, their very English accent coming down the line. ‘None for 10,’ I told them one day. ‘That’s 10 for none in your language.’ ‘Oh, I see,’ was the reply. And there were calls from sundry others; after Greg Matthews started playing his father would call from time to time for an update. I always loved taking these calls. On another occasion, Ken Sutcliffe and a crew from Channel 9 came up to do a news feature on the board. ‘Not a bad school holiday job,’ was Ken’s remark to me. Even he was impressed.

If you want more from Around The Grounds go here

Thanks to Bad Apple Press for providing this extract.